The Hermitage and its extraordinary evacuation during WWII

The events describing the siege of Leningrad and its staggering number of casualties (estimated at over three million on the Russian side) have been well documented. The loss of life and destruction are considered to be one of the costliest in history. Hitler’s orders were to destroy the city and its entire population. According to a directive sent to Army Group North on the 29th of September 1941, "After the defeat of Soviet Russia there can be no interest in the continued existence of this large urban centre. [...] Following the city's encirclement, requests for surrender negotiations shall be denied, since the problem of relocating and feeding the population cannot and should not be solved by us. In this war for our very existence, we can have no interest in maintaining even a part of this very large urban population." (1)

It would be safe to say that the Hermitage and its collection could not have survived all the bombardment, battles, fires and looting of Leningrad under a complete Nazi occupation. We can see the destruction endured by all of the palaces that were outside the city’s circle in many period photographs. Hitler ordered the looting and destruction of the Imperial Palaces of “ Catherine Palace -Tsarskoye Selo, Peterhof Palace, Ropsha, Strelna, Gatchina, and other historic landmarks located outside the city's defensive perimeter, with many art collections transported to Germany.” (2)

The operation to protect, package and evacuate most of the Hermitage’s collection that counted over two and a half million objects must be one of the largest and most difficult art rescues in history. A series of events dating back to the 19th century contributed to the success of the speedy and “officially” unplanned evacuation.

Until the last part of the 19th century, the Hermitage collection was considered and administered as the private property of the Czars. Access to it was restricted to very few and its display organized to a large extent on different decorative groups. The lack of apparent interest in large acquisitions for the Hermitage at that time proved to be one of those events that contributed to the collection’s survival. “Under Alexander II (r. 1855-1881), the Hermitage Museum became an independent government administration. During his reign, and those of Alexander III (r.1881-1894) and Nicholas II (r. 1894-1917), the Czars had little involvement with the organization and acquisitions of the Hermitage. While the collection grew little during the late Romanov era, it was an important period for art historians. The curators used this time to organize and catalogue the collection.” (3)

For the first time in its history, the Hermitage had a careful, detailed and scholarly itemization of its collections. Such a list was to prove crucial in any plans to package and transport millions of objects. Second, for some unknown reason, the director of the Hermitage, Joseph Abgarovich Orbeli began to prepare for the evacuation even before World War II started. “In 1937, the Sampson Cathedral was leased to the museum, where a team of joiners pounded boxes of certain sizes for specific exhibits (objects). This work took four years. What is most interesting, is that no one knew about this, except Orbeli and the head of the special department, Alexander Tarasov. Probably, the museum workers guessed, although the funds were checked quite often. But when the war began, thousands of boxes and packaging material somehow quietly appeared in the Hermitage. Interestingly, workers even knew which boxes and which exit to use to remove the pieces.

Everything was very well planned: all the necessary documentation was prepared in advance, a schedule for the order and place of packing was created, a route for transporting them was developed - which stairs to go down, through which staircase and the sequences to take them out, and so on, says the leading researcher at the Department of History and restoration of architectural monuments of the Hermitage Svetlana Yanchenko.” (4)

By the beginning of June 1941 as the Nazi troops approached Russia, Director Orbeli started seeking orders from Moscow as to the protection of the Hermitage’s collection. Lane Bailey in his Honor Theses (3) mentions that Stalin specifically ordered Director Orbeli not to start packing or even accumulating packing materials for the eventual evacuation. These actions could have given the impression of desperation or defeatism which was to be avoided at all costs. On Sunday, June 22, 1941, the Nazi forces invaded Russia. Without any orders from Moscow, Director Orbeli directed all of his employees to start packing that same evening (5). By the time the green light arrived from Moscow, Orbeli and his staff were way ahead of the game with more than half a million pieces of art taken from the Museum’s galleries and packed in boxes. (6)

The fact that thousands of prepared and numbered boxes already existed, secretly stored, numbered and specifically made for most of the collection; together with the accumulated packing materials at a nearby Cathedral is certainly an incredible accomplishment of Director Orbeli and those that may have known but never discussed.

To date, we have a detailed and highly organized list of the collection available, the availability of prepared and numbered boxes, stored packaging material and specific detailed plans for moving all of the boxes through the Hermitage’s galleries to their evacuation. However, Director Orbeli and his staff were to perform many more actions to salvage the art.

Two full trains were able to leave Leningrad with the Hermitage’s treasures. The first one departed on July 1, 1941. “… loaded the crates under heavy guard on a hastily assembled train consisting of two locomotives, an armored car for the most valuable objects, four Pullmans for other special treasures, and twenty-two freight cars filled with canvases and statues. Two flatcars with antiaircraft batteries and one passenger car filled with military guards provided security for the train.

The train quietly departed on July 1, preceded by a separate locomotive to clear the tracks. In the interest of security, the train 's engineers did not even know their final destination. The train eventually arrived near Sverdlovsk (Yekaterinburg), a Ural Mountain city in south-central Russia, where it remained until August 1945.” (6)

“A second train carried away another 700,000 exhibits on July 20, but more than one million artifacts remained in storage. Orbeli ordered preparations for the evacuation of the final collections, but curators had only packed 350 crates by mid-August when work stopped.” (7)

A third planned train could never leave since the Nazi troops had closed all access to the city. Nearly one and a half million objects were evacuated to Sverdlovsk 1,500 miles away from Leningrad.

All remaining objects were transferred to the lower floors, basement and into hastily constructed bomb shelters which were also prepared for the staff, their families, and others in the academic and cultural environment. The evacuated art returned to the Hermitage on October 10, 1945. (8)

One collection of objects could not be moved out of their assigned places in the galleries. The fabulous set of monumental Russian Empire Style Vases that were so large and so heavy (some of them weighing in excess of 10 tons) remained.

The State Hermitage Museum possesses an impressive collection of monumental vases made of Russian semi-precious stones mounted in gilt-bronze. “These vases took years to produce. Once the stone had been selected - rich dark-blue lapis lazuli, jasper, pink rhodonite or various porphyries from the Ural Mountains - a craftsman would begin to turn the stone to designs set by the Tsar's Imperial Cabinet. Often, these designs would be the work of the foremost architects of the day. When the vases were completed they were exhibited on the Jordan staircase of the Winter Palace at Christmas and Easter. The Tsar would pick the pieces he wanted and the rest were given away as gifts. Among the most treasured of these vases were those made of lush green Russian malachite, created in a laborious mosaic technique.” (9)

Photographs exist that show these vases standing defiantly in the middle of the damaged galleries, some with broken windows, open ceilings and holes on their floors. For us, those images show the permanence and endurance of these monumental vases.

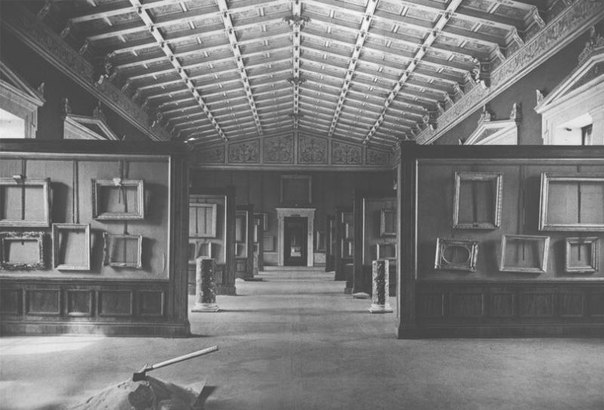

Over two thousand people lived in the shelters of the Hermitage and the rest of the Winter Palace during the siege. After each bombardment, soldiers and those that lived there boarded the destroyed windows, cleaned the debris and tried to salvage chandeliers and ornaments from the walls. Director Orbeli and other guides managed to give tours to the soldiers describing the paintings that would have been hanging from those empty frames in the different galleries. One example of the situation inside the Hermitage’s shelters was narrated as follows: “By this time the daily bread ration in Leningrad was 125 grams per person. This sketch depicts a thin, bony palm stretched out holding four small crumbs of bread. The fingers are long, thin, and crooked, perhaps representing rheumatism that many Hermitage workers, including Director Orbeli, suffered from throughout the siege”. (10)

There were countless acts of bravery displayed to protect and salvage the art collection during those months of the siege. Ludmilla Voronikhina, an art historian at the Hermitage tells one of them: “In the winter, freezing water from a burst pipe flooded the cellar. A team of elderly lady museum guides came to the rescue, descending to the ice-cold underground lake in total darkness, treading gingerly in rubber waders to avoid crushing the submerged vases, dinner services, and Meissen shepherdesses underfoot.” (11)

The Hermitage lost some treasures and sustained enormous damage during the siege, but the incredible foresight, planning, organization and hard work of a very small staff that was helped by soldiers, sailors, and citizens of Leningrad, saved one of the most important collections of art in the world. A visit to the State Hermitage Museum today should also be a celebration of the human spirit, and gratitude for the many that helped build, preserve and protect an immense collection of art in the face of darkness.

Director Orbeli’s words summarize that spirit in this short entry of his diary “On June 22, 1941, all employees of the Hermitage were called to the museum. Hermitage researchers, security personnel, and technical employees all took part in the packaging, spending no more than an hour a day on food and rest. And from the second day, hundreds of people who loved the Hermitage came to our aid ... We had to force these people to eat and rest by order. The Hermitage was dearer to them than their strength and health.” (12)

Meb3

(1) Reid, Anna (2011), Leningrad: The Epic Siege of World War II Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8027-7882-6.

(2) Nicholas, Lynn H. (1995). The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe's Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War. Vintage Books.

(3) Protecting the Art of Leningrad: The Survival of the Hermitage Museum during the Great Patriotic War. Lane Bailey. Honor Theses. Ouachita Baptist University. 1997

(4) The revival of the Hermitage after the war: secret boxes, ruined halls and a feat of museum workers. Prepared by Alla Bortnikova / IA Dialog. April 8, 2019.

(5) Harrison E. Salisbury, The Nine Hundred Days: The Siege of Leningrad (New York: Harper and Row, 1969)

(6) L. Y. Livshitz, ed., Ermitazh v Gody Voiny (Leningrad: Publishing Council of the State Hermitage, 1987)

(7) Joseph Orbeli, Director of the State Hermitage, "Instructions, 22 June 1941 " (Leningrad: The State Hermitage, 1941)

(8) L. Y. Livshitz, ed., Ermitazh v Gody Voiny (Leningrad: Publishing Council of the State

Hermitage, 1987).

(9) Burton Holmes Travelogues. Volume Eight, 1914. The Travelogue Bureau

(10) Nikolsky, A.C. Leningradskaya Album: Rysukny, Gravyory, Proekty, Voiny (“Let Leningrad Album: illustrations, Prints, and Graphs from War Years"). Leningrad Office, 1984.

(11) Sebastian Harcome, Labour of Love, Art in Russia….NewStatemanAmerica, August 8, 2005.

(12) Director of the Hermitage Academician I. A. Orbeli. Hermitage during the blockade. Archival material. Science and culture. Nonfictional Tales of War. October 3, 2014.